The bench press is arguably the most popular weightlifting exercise in the world. It involves a lifter lying flat on a bench, hands directly above the shoulders, gripping a barbell and moving it up and down. It is so common, in fact, that virtually every gym in the world has at least one bench press rack. The bench press is one of the most effective, time-tested exercises to build upper-body pressing strength, strengthening the pectoralis majors (chest), shoulders and triceps muscles all at once if done correctly. In this article, we will explore what it is, its history, and how to perform a bench press.

What is a bench press?

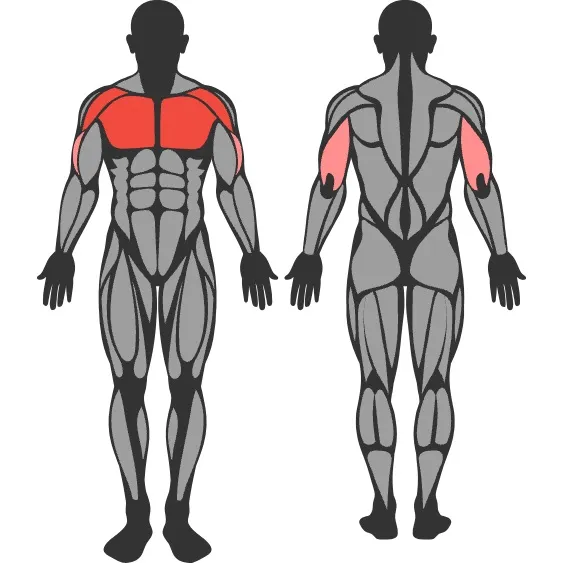

A bench press is a popular weightlifting exercise that uses a barbell and a bench. It primarily trains the chest, triceps and anterior deltoids.

In a bench press, the lifter lies flat on a bench (not exactly flat, we’ll get to this in the how-to section), with their feet planted on the ground, arms up directly over the shoulders and hands gripping a barbell.

In a bench press, the barbell moves up and down in an arc (more on this in the how-to section). The triceps, anterior deltoids (front part of shoulders) and chest are all active throughout the movement, but vary in activation in different parts of the movement. The chest is most active at the bottom of the movement, where the barbell is in contact with the sternum. The anterior deltoids are most active at the midpoint of the movement. The triceps are most active near the top half of the movement. These muscles contract eccentrically (active lengthening) on the way down, isometrically (active static hold) during the short pause, and concentrically (active shortening) on the way up.

The bench press is one of the three main lifts in powerlifting: squat, deadlift, and bench press. It places incredible load on the upper body compared to other upper body movements For this reason, it is a large contributor to one of the most common weightlifting injuries, an injured shoulder (or shoulders. More on this in the how-to section).

The history of the bench press

1800s

Lifters, mainly strongmen at the time, trained with overhead presses. They did not perform the bench press as benches were rare and lying flat on the ground to press up a barbell reduced chest activation.

1920s – 1930s

With the rising popularity of commercial gyms, lifters were starting to use raised benches or boxes to press up a barbell to increase chest activation. However, the bench press was still informal and uncommon.

1940s – 1950s

The bench press grew exponentially in popularity due to the rise of commercial gyms, and improved barbell and bench press rack design.

1960s – 1970s

With the emergence of powerlifting, the bench press became one of its three main lifts. Powerlifting rules standardized grip width, pauses, bar path and lockout, providing form guidance to lifters.

1980s – Now

With the rise of bodybuilding and weightlifting, the bench press continues to grow in popularity, and multiple new variations have emerged – the incline bench press, decline bench press, etc.

How to perform the bench press

Note on safety: While the bench press is an incredibly effective exercise for strength and hypertrophy (increase of size), it also places an incredible load on the upper body, and when combined with the lifter’s position during the lift, it can be quite dangerous. There have been cases where the barbell crushed the lifter’s chest or neck after the lifter was too fatigued to press the barbell back up.

Step 1: Setup

Like buildings (and every other exercise in the world), the bench press starts from the ground up. This may seem counterintuitive because you are lying on a bench on your back. But in the bench press, the legs play a crucial role, mainly in stabilizing the whole body.

When performing the bench press, make sure you are wearing grippy & stable shoes. Also, the barbell should be racked at a height where you can comfortably unrack it without having to do a partial rep. Furthermore, bench pressing heavily alone is dangerous and not recommended, unless you are using safety bars. If not, use a spotter when benching heavy. When bench pressing, it is important to never use barbell collars. If you’ve ended up crushed under a heavy barbell without a spotter or safety bars, you can slide the plates off the barbell, one side at a time. This is a last resort, and it will save your life. If you cannot do this because you used barbell collars, you might lose your life.

Start by lying flat on your back on a bench. Plant your feet on the ground, with your shins vertical from the floor. Feet width varies by preference, but anywhere between shoulder width and double the shoulder width is a good place to start. Your eyes should be directly below the barbell.

Then, squeeze your shoulder blades together and depress them down to your torso as if you were trying to make your neck longer. They should stay in this position throughout the entire movement.

Arch your back, enough so that you can fit a flat hand between your back and the bench. The size of the arch varies by preference and mobility, so play around to see where you feel most comfortable. Your scapula should lie flat on the bench and should feel secure in that position. The arch increases strength, stability, and protects the shoulder joints.

Then, establish tension in your body by pushing into and out to the ground with your feet. Do not push straight up like a glute bridge; push into and out like a leg extension. This is called leg drive, and it helps maintain your arch and balance.

Step 2: Grip

Do not just simply grab the barbell. Place your palms at the bottom of the barbell, directly above the bones of your wrist. Then, rotate your wrist slightly inward (pronation) until you can comfortably grab the barbell directly above the bones of your wrist. This allows for efficient power transfer and protects the wrists.

Occasionally, you will see a lifter using a thumbless grip, otherwise known as a suicide grip. This is when you grab the bar with the thumbs on top of the barbell, instead of under it. When bench pressing, it is imperative that you never, ever, ever use the suicide grip. It is called a suicide grip for a reason, and there is no benefit gained from making the world’s most dangerous exercise even more perilous with this stupid grip. It is often used by lifters to grip the barbell directly on top of the bones of your wrist, which is a mechanically efficient position. However, as discussed above, this position is achievable with a normal grip, simply by slightly pronating the hands. Furthermore, although the thumbless grip gets into the same mechanically efficient position as the standard grip, it reduces power transfer efficiency by limiting your grip strength. You cannot move what you grip lightly; a strong grip allows you to move heavy weights by increasing stability. Plus, there is also the obvious possibility of the barbell slipping from your hands onto your chest or neck.

The width of your grip varies by preference and purpose, but for a standard bench press, a few inches outside shoulder width is ideal for most people. Make sure your forearms are vertical at the bottom of the rep. If they are not, the grip width is incorrect. Do not unrack the barbell yet.

Step 3: Unracking

Before you unrack the barbell, make sure your upper back is still tight and your legs active. Engage your lats by actively trying to bend the bar in half; this will create stability. Take a deep breath (valsalva maneuver), and unrack the barbell, as if you were rowing it from the rack. Don’t try to push it; this often leads to loss of scapular stability.

With heavy benches, get your spotter to help you unrack the barbell. The disadvantageous position you are in when unracking becomes a problem quickly as you get stronger, to the point where it may be limiting your strength. Plus, it can be dangerous.

After you unrack, make sure your arms are straight and the bar is directly over the shoulder joint.

Step 4: The Eccentric (Descent)

It is finally time to lower the barbell. But before that, pick a spot in the ceiling to fix your eyes upon. Use this spot as a reference to help you bring the bar back up to the exact same position every rep. If your eyes are fixed on the bar, the bar path will not be consistent.

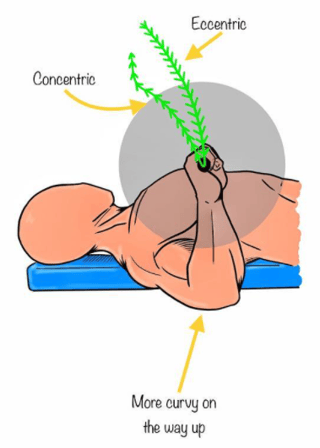

The bench press is a unique exercise because its bar path is an arc, meaning the bar moves horizontally as well as vertically. This arc is extremely important when bench pressing because it will protect your shoulders (though at the cost of mechanical efficiency. But injured shoulders are far worse than a weaker bench).

Take a deep breath and brace your core as if you were about to get punched in the stomach (valsalva maneuver). Now lower the bar slowly. And as you lower the bar, your upper arm (humerus bones) should be around 70 – 45 degrees relative to the ribcage (keep in mind, the closer your arms are to 90 degrees, the more chest activation you will get). This ensures that the bar path is correct, given your forearms stay vertical the entire rep. Maintain tension in the lats, upper back, core and legs throughout the rep, every rep. At the bottom, the bar should touch your mid to lower sternum, depending on arm angle. If the bar does not touch, the rep is invalid. If you cannot touch your sternum with the bar without pain, do not bench press. Remember, the bar should move in an arc, not straight up and down.

As you lower the bar, it is important that you do not drop it on your chest. This will lead to pec tears, an injured shoulder, and a painful ribcage. The eccentric should last one second to eight seconds. In other words, make sure to control the weight on the way down.

Step 5: The Concentric (Ascent)

When the bar touches your sternum at the bottom, do not press it back up immediately. Pause for a brief moment, and push. We are tempted to press it back up immediately because of the stretch reflex; you can lift more weight that way. But to build raw strength, a pause is incorporated at the bottom to ensure you’re not abusing the stretch reflex. It doesn’t need to be a long pause; just enough to avoid using the stretch reflex.

When you do push the bar back up, ensure your body is still tight: leg drive, scapular tension, valsalva maneuver and the stabilizing muscles of the back should all be engaged as they were at the start. Also, do not breathe until the bar is at lockout (you shouldn’t be able to breathe properly during the rep anyway. If you can, you are not tight enough.)

Some lifters tend to push the back of their head against the bench on the concentric. Avoid doing this, as it will hurt your neck. If you have had this bad habit for a while, try lifting your head throughout the entire set.

Furthermore, on the concentric, make sure to maintain your upper arm angle. Some lifters tend to let their elbows drift outward beyond the angle of 70 degrees, leading them to slowly saw off the tendons of their rotator cuffs (otherwise known as impingement). If you find yourself doing this, lower the weight.

Technicalities aside, push with everything you’ve got, and utilize the tension in your body to transfer energy like a bow. Do not lose tension!

When you reach the top, return to the original position, using the chosen spot on the ceiling as a reference. If your elbows do not hyperextend, you can safely lock out your arms gently. Do not throw the barbell up and leave your elbows to absorb the momentum of the barbell if you do not want to end up in the hospital. If your elbows do hyperextend (beyond 180 degrees), a soft lockout is usually safe, given the degree of hyperextension is not severe. However, I strongly advise you to avoid locking out in this case, because one, it hurts to watch, and two, you never know.

If you are doing more reps, you can finally exhale at the top and inhale to reestablish tension before doing another rep. Another option is to hold your breath until the end of your set to avoid losing tension, but the discomfort from the hypoxia is often too distracting for most people.

Step 6: Reracking

When you have completed your set, it is time to rerack. This is usually when beginner bench pressers get injured. They miss the rack on one side and the barbell whips to one side as the plates slide off the other. Not only is this extremely loud, but it will also hurt your shoulders.

When reracking, make sure you are at lockout. You do not want the barbell to be positioned too low when reracking. Control the weight on the way to the rack, and make sure you hit the back of the rack before the bottom, to ensure you do not miss it. If you are benching heavy, the spotter should help you rerack.

After the barbell is properly in the rack, you can finally relax and lose tension.

Congratulations, you have completed a set of bench press.

Spotting a bench press

Bad spotters (i.e. people who watch over lifters) can make the bench press even more dangerous. Therefore, spotters need to be competent and well-informed about the rules of spotting a bench press.

Rule #1: If the spotter touches the bar during the rep, the rep is invalid, regardless of how much help they gave. Make sure the spotter only intervenes when the barbell starts dropping back down, or when you signal to them to intervene.

Rule #2: The spotter should help you, not take over. This is an obvious rule, but if for some reason you give up completely and stop applying force to the bar, the spotter cannot possibly get the bar back up without herniating a few discs and dislocating both of their shoulders. So when you reach failure, always help the spotter.

Rule #3: One spotter is usually enough and should be used over three spotters. Unless you are in a powerlifting meet or a competent powerlifting gym, a three-person spot is more dangerous than a one-person spot for obvious reasons.

Rule #4: If you cannot find a competent and well-informed spotter, use safety bars. Incompetent spotters make the bench press even more dangerous because they do not know what they are doing. If your friend is spotting you, make sure they know how to spot a bench press.

FAQs on the Bench Press

How many reps should I do per set? – For strength, 1 – 6 reps is ideal. For hypertrophy, 6 – 30 reps is ideal. Both rep ranges build strength and trigger hypertrophy, but you will gain more strength if you do lower rep ranges closer to your 1 rep max.

Why do my shoulders hurt when Bench Pressing? – Given that your technique is perfect, shoulder pain can be caused by weakness in the shoulder stabilisers: the rotator cuffs, shoulders, and lower traps. I recommend doing a few sets of external rotations at the end of every bench press workout to strengthen your rotator cuffs. But make sure to not to overtrain them.

Why is the barbell not stable during the Bench Press? Why does it rotate and move where it’s not supposed to? – Most beginners experience this when bench pressing. Your body is still getting used to stabilizing the barbell on the bench press. You will experience this again when you try dumbbell bench presses for the first time. If you have good technique, you will gain stability over time. If you are not a beginner, it could be caused by poor technique. More specifically, a lack of tension.